Jubilee

From February 7 to April 5, 2019

Opening on February 7 at 7 pm

Justin Bennett, Eleni Kamma, Vincent Meessen, Jasper Rigole, Vermeir & Heiremans

Video programme presented in echo with Vincent Meessens’ exhibition at the Leonard and Bina Ellen gallery, from November 17, 2018 to February 23, 2019.

Jubilee ― platform for artistic research and production

Jubilee was first established in 2012 as a dialogue among artists and cultural workers who consider collaboration and artistic research as essential ways of working. Since then, it has evolved into an artist-run platform that provides continuous support for the work of six artists, while hosting other artworkers on a project base instigated by the platform’s collective research. Jubilee’s focus is twofold. First, it is an organisation for the production of the work of the member artists. Since 2015, these are Justin Bennett, Eleni Kamma, Vincent Meessen, Jasper Rigole, and Vermeir & Heiremans. Second, their shared interests lead to collective, performative research projects, involving collaborations with artists, curators, academic researchers and other professionals, art schools, universities and (art) institutions, and focus on the conditions of artistic practice.

For the Jubilee artists, collectivizing and sharing partnerships has been an opportunity to use the benefits of networks, visibility and other resources, while alleviating the responsibilities of fundraising, bookkeeping and legal costs. But Jubilee remains in the first place a platform for content exchange and discussion. Together, the artists constitute Jubilee’s collective artistic direction. Within their practices, Jubilee’s member artists work in diverse media and on a variety of topics, but always on a basis of collaborative research that brings in transversal knowledge from a wide range of perspectives. — www.jubilee-art.org

PROGRAMME — 127 minutes

(Schedule: noon ― 2:30 pm)

Vermeir & Heiremans, The Good Life, a guided tour (2009)

— 17 min.

In the background, technicians are installing a prestigious exhibition, whilst a smartly dressed lady is guiding a group of people around a series of pristine white spaces, some of them filled with crates and wrapped-up paintings. Along the way she not only comments on the art but also reveals the building to her audience from a unique perspective. Describing interiors, great views and the city’s vibrant opportunities, the lady turns out to be an estate agent who is selling an up-market architectural proposal and a lifestyle that grafts the ‘value’ of art with its institutions. Moving through the labyrinthine building, she finds herself lost in narrow corridors and staircases. Meanwhile the future development projects itself into the group’s collective imagination, fed by the visionary architectural model on display.

The Good Life, a guided tour redefines our perception of the art institution and raises our awareness of its part in the ‘creative city’, a scenario that is being played out in metropoles around the globe. The woman in the video who first seems to be an exhibition guide transforms into a real estate agent selling the visionary architectural proposal. Her hyperbolic language is derived from clippings from the Bristol Architecture Institute press archive, real estate advertisements & brochures, etc. The immaculate spaces in which she walks seem to be situated in one big museum, whereas in fact the building in the video consists of different white cubes located in England and Belgium. The apparently ‘neutral’ frame of the gallery space which envelopes the spiritual and cultural heritage of our society, recedes in favour of that of a real estate opportunity. The estate agent is the embodiment of the denial of any possible negative impact that the creative race between cities in a neo-liberal context might generate. Through a generic language that excludes any notion of ‘gentrification’, her hyperbolic tour creates an exclusive identity.

The film’s elaborate treatment of sound – as well as the absence of it – disrupts the untenable perfection of the architecture, and its mediated forms, making the emptiness of the building sensible, which actually is what the estate agent is selling: a lifestyle fantasy projected on an empty shell.

Commissioned by: ARNOLFINI Art Centre, Bristol (UK)

Production: Limited Editions (BE)

Support: Flanders Audiovisual Fund ― VAF

Distribution: Jubilee (BE), Argos (BE)

Vincent Meessen, One.Two.Three (single channel version) (2016) — 30 min.

In One.Two.Three, Vincent Meessen begins by circumventing the trap of the mythology of the Situationist International, the last international avant-garde movement of Western Modernity, in which Guy Debord has been consecrated as the hero and epicentre of a revolution. Instead, the work revisits a part of the history of this movement which has to date been ignored. The starting point for the work is the discovery, in the archives of the Belgian Situationist Raoul Vaneigem, of the lyrics to a protest song that Congolese Situationist Joseph M’Belolo Ya M’Piku composed in May 1968. Working with M’Belolo and young musicians in Kinshasa, Vincent Meessen has produced a new rendition of the song. The fragmented cinematographic display of the work offers a spatial translation of this collective arrangement of subjectivities.

The multi-coloured labyrinth of Un Deux Trois, the club that was once home to the world-famous OK Jazz orchestra led by Franco Luambo, a key figure of artistic modernity in the Congo, offers the perfect setting for a musical dérive. Against the background of Congolese rumba, a popular and hybrid genre par excellence, threatened vernacular architecture and revolutionary rhetorics of the past, the film puts to music the narrative of unexpected meetings and one of the forms that resulted from it: M’Belolo’s song.

Transformed into an experimental space by musicians who, in the course of their perambulations, try to get attuned to each other, the club becomes an echo chamber for the impasses of history and the unfinished promises of revolutionary theory. And while M’Belolo Ya M’Piku rediscovers the song he had lost, popular uprisings break out in Kinshasa just outside of the walls of the rumba club. In spite of the cycle of violence and the militarization of everyday life, a space is created for play, polyphony and dance. The rendition that matters in One.Two.Three is perhaps less the recovery of the song than the rendition of emancipation itself, which, irresolute by nature, remains condemned to an ‘untimely repetition’.

Created for the Belgian Pavilion at the 56th Venice Biennale

Commissioned by: Fédération Wallonie-Bruxelles (BE)

Production: Normal (BE)

Support: Africalia, Willame Foundation, Flanders - State of the Art, Wiels, CWB Kinshasa

Distribution: Jubilee (BE)

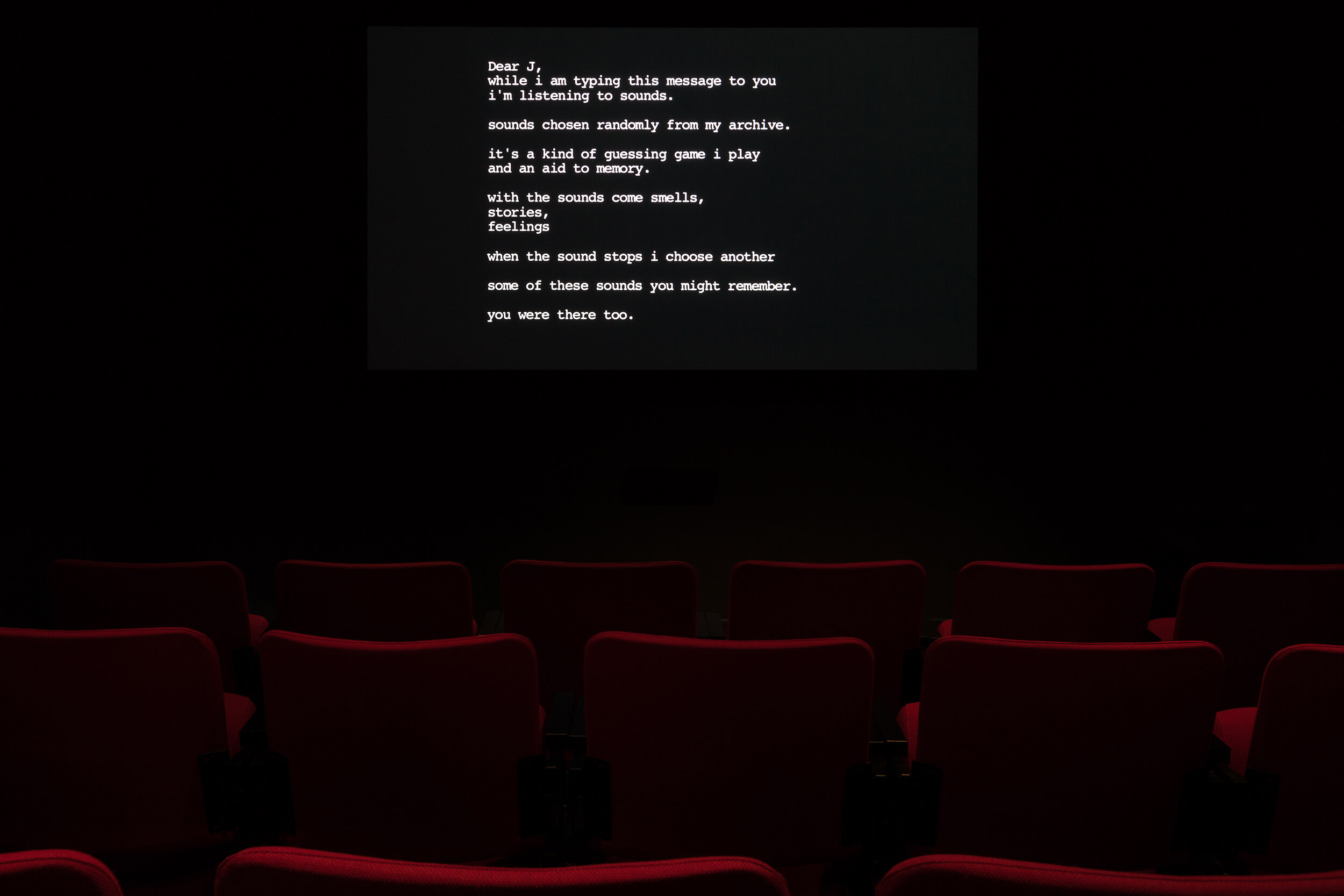

Justin Bennett, Raw Materials (2011) — 23 min.

In Raw Materials Justin Bennett asks what it is possible to hear within field recordings. The protagonist types a letter while listening to sounds from his archive. He writes of the ability of sound to trigger memories, to conjure up events, places and emotions. He is playing a game with himself and the audience, implicating us: “Do you remember? You were there too.” Can we listen to a sound archive as a personal diary, as a fictional narrative or as legal evidence? Is the maker a listener, an actor or an author? And which tapes did he erase, and why?

Bennett’s recording of sound is comparable with the shooting of video. He uses various microphones to change perspectives – like camera lenses. The microphones – the listener’s points-of-hearing – move through a city, a street, a windy Russian tundra, or the different-sounding spaces of a building.

In many of Bennett’s works and installations sound is complemented by video images that affect the experience of the visitor differently again. In some of his research projects the audiovisual material is juxtaposed with voice-overs and drawings, mapping space, movement, sound, magnetic fields, and so forth, through language and diagrams. Thus, a reciprocity is created between various forms of expression: a drawing or a text can be a score; and sound and image become ways of drawing and writing.

This way, Bennett’s work is also a research into sound and image as specific media, and an exploration of the ways in which they can be used and experienced. His way of working sparkles unexpected complementarities, synaesthetics, collisions and manipulations of the mind.

Production: Justin Bennett (NL)

Support: Mondriaan Fonds (NL)

Distribution: ARGOS, Centre for Art and Media, Brussels (BE), Jubilee (BE)

Eleni Kamma, Yar bana bir eğlence. Notes on Parrhesia (2015)

— 37 min.

In her first cinematographic film, Eleni Kamma revisits the tradition of the Karagöz Theatre and its role in the creation of a political voice.

Although Karagöz is a local character symbolizing the “little man” within the limits of the Ottoman Empire, he belongs to a larger puppet theatre family. He speaks of what the people want to hear and what the people want to say. Until 1870, despite the “absolute monarchy and a totalitarian regime”, Karagöz “defied the censorship, enjoying an unlimited freedom”. Through the use of empty phrases, the illogical, the surrealistic, extreme obscenity and repetition, Karagöz theatre was often used as a political weapon to criticize local political and social abuse. By 1923, this multi-voiced empire gave way to a Turkish-speaking republic within which the caricatures of ethnic characters no longer made sense. With the rise of new media, the popularity of Karagöz and Orta Oyunu declined even further.

Yar bana bir eğlence. Notes on Parrhesia reflects on the term “parrhesia”, which implies not only freedom of speech, but also the obligation to speak the truth for the common good, even at personal risk, by questioning how the notion of entertainment relates to personal expression and public participation.

This is where the artist links to the Gezi Park protests in 2013, in which humor and creativity were key elements in mocking the political regimes. Filmic fragments from National Cypriot television archive alternate with the voices of Cypriot, Greek and Turkish Karagöz masters discussing language, history, the tools and the political role of the medium.

The film is a visual essay in which pressing contemporary political matters intertwine with history and abstraction; and in which meticulousness of research meets with poetics of associations. How to move forward? Can we learn something from the old masters? At times the gaze is directed back to the viewer. To speak your mind, you must first overcome fear by taking a deep breath.

Production: Jubilee (BE), Netwerk center for contemporary Art (BE)

Support: Mondrian Fund, NiMAC (Nicosia Municipal Arts Center), PiST/// Istanbul, SoundImageCulture (SIC), Theater aan het Vrijthof, Flanders Audiovisual Fund ― VAF

Distribution: Jubilee (BE)

Jasper Rigole, Temps Mort (2010) — 20 min.

The majority of home movies are shot on holidays. When people return from their travels, they are very curious about the images they have shot. Often, however, there is still some film left in the camera.

The film Temps Mort uses these little fragments filmed in order to fill the reel, before being able to have them developed. These shots of empty gardens, sleeping pets and flowerbeds are, in Jasper Rigole’s eyes, more real than any home movie fragment. The term “temps mort” is also a reference to Michelangelo Antonioni’s films. The term was used to describe the way Antonioni’s camera frequently wanders to and holds on apparently insignificant details in the frame, non-narrativized elements that have the effect of draining significance from the events that have just unfolded.

Rigole is the founder and conservator of the (fictitious) International Institute for the Conservation, Archiving, and Distribution of Other People’s Memories (2004). This ongoing multimedia project is an original and lively collection of linear films and multimedia art projects created out of found films, photographs, and documents the artist has gathered over the years. As an ongoing artistic project, it is in itself a constantly growing virtual archive for the images Rigole has recycled, a fraction of the huge analog film archive Rigole has built from anonymous 8mm images he has collected at auctions, in secondhand stores, and at flea markets. He uses these found home movies to make imaginary films that situate these images from the past in a contemporary context and aesthetic, combining elements from both literary and referential genres.

His style can best be described as a filmic form of experimental life-writing that calls to mind the work of Jorge Luis Borges and Georges Perec, two important sources of inspiration for Rigole.

Production: Jasper Rigole (BE)

Support: Europe Home Movies Net (EHMN) (IT), Flanders - State of the Art (BE)

Distribution: Jubilee (BE)

Dazibao thanks the artists for their generous collaboration as well as its advisory programming committee for its support.

Dazibao receives financial support from the Conseil des arts et des lettres du Québec, the Canada Council for the Arts, the Conseil des arts de Montréal, the Ministère de la Culture et des Communications and the Ville de Montréal.